Vapor barriers in walls, why polyethylene can be problematic

It would probably surprise many home builders to hear what really causes moisture accumulation in walls, and what to do to prevent it. An understanding of how water vapor moves through walls is important, so a good place to start would be with our page explaining moisture movement in homes (see related articles below).

The traditional approach to preventing water vapor from penetrating walls in homes is a 6 mil polyethylene vapour barrier, or 'vapor barrier' for our southern neighbours. This is an ideal building practice in the extreme northern communities of Canada, less so as you come further south. Despite it being used extensively in residential construction, it can be overkill in most Canadian homes, and can cause problems of its own.

"One of the problems in the building industry is that we have a spreading 'cult-like' mentality that worships at the 'church of polyethylene'. This cult views the answer to all moisture problems as the installation of a polyethylene vapor barrier on the inside of buildings. This cult is responsible for many more building failures than building successes. It's time that the cult deprogramming started."

- Joe Lstiburek, Principal of Building Science Corporation

The USA & Canada has many climatic zones, so there is not one building envelope that can possibly serve them all. The automatic installation of a polyethylene vapour barrier in every home from the Hudson Bay to the vineyards of Southern Ontario to the deserts of Arizona meets the state & provincial building codes, but completely ignores the reality of how different those climates are.

Many parts of the country can range from extreme cold to extreme heat and humidity, with temperatures that vary as much as 60 degrees Celsius or more. In areas like that, the vapour barrier that works great in February isn't doing you any favours in July. During those 30+° Celsius days with relative humidity levels upwards of 80% and an indoor air-conditioned environment some 10 degrees cooler, that vapour barrier is on the wrong side.

Is the solution then to not install a vapour barrier? No, but since there isn't a perfect solution that meets the needs of both climatic extremes, we should find a solution that at least takes them both into account.

The vast majority of Americans & Canadians live in a temperate climate, so for most of us a vapour barrier (or more accurately semi-permeable vapor retarder) that allows a certain amount of water vapour to pass through a wall could actually serve us better over the course of the year.

As warm, humid air cools, air molecules shrink and squeeze out the moisture. This can be a problem if it happens inside your walls, so vapour barriers are there to mitigate that.

In order to prevent condensation from forming, a vapour barrier should be placed on the warm side of your insulation to stop warm, moist air from condensing on a cold surface inside your wall.

In cold climates like Canada, for most of the year the vapour barrier should be on the inside of the insulation. In hot climates like the southern U.S. for example, it should be installed on the outside of the insulation.

In both cases, the vapour barrier is tasked with preventing warm, humid air from shedding its moisture as it meets a cool surface, no matter which direction it is travelling.

The most important thing to realize is that there is no fixed rule regarding vapor barriers. Building practices should always be determined by the climate zone in which you are building.

Understanding vapor barriers:

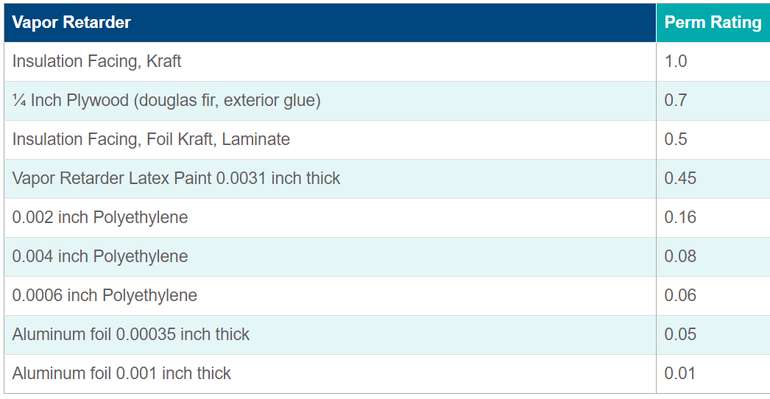

The National Building Code of Canada stipulates that for residential buildings, a vapour barrier must have a water vapour permeance of less than 60 ng/Pa*s*m2 or 1.0 Perm. That means that no more than 60 nanograms of water vapour can pass through a square meter of the material in one second. Nanograms are pretty small by the way, that's one billionth of a gram.

Traditionally, a polyethylene vapour barrier (with a vapour permeance rating of 3.4 ng) is installed behind the drywall in new Canadian homes. In fact, you would be hard pressed to find a home being built in Canada right now that does not have it, or something equally impermeable to moisture. This doesn't mean that there aren't other options out there, they just aren't being applied.

In the US any material that has a perm rating of 1 or less is considered to be an adequate vapor retarder for residential construction. As requirements vary between states we suggest giving your local permit office a call to establish their recommendations. The perm rating is a measure of the diffusion of water vapor through a material & the table below shows the perm rating of some common building materials that are consistent with the ASHRAE Handbook of Fundamentals and other industry sources.

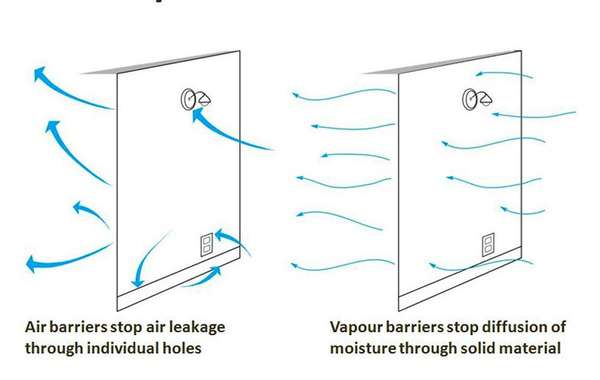

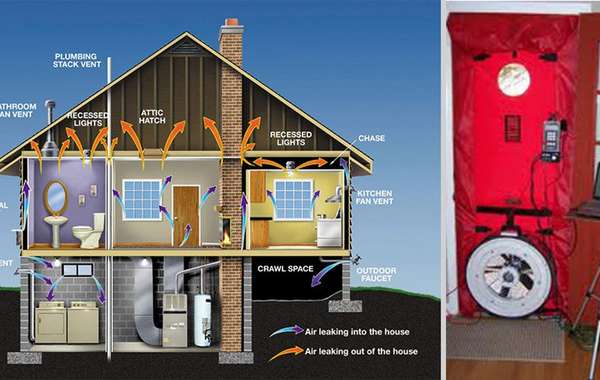

The problem is largely because the 6 mil poly that gets installed as a vapour barrier is mistaken for, and almost entirely relied upon to act as the air barrier. The purpose of the two barriers should not be confused - the job of the vapour barrier is to control vapour diffusion, the job of the air barrier is to control air leakage.

6 mil poly can work effectively as an air barrier if it is carefully sealed, but so can other materials. Well-sealed drywall in itself makes a great air barrier. But unless you install polyethylene with the express purpose of it being an air barrier, it likely isn't doing the job. And in fact, the term 'air barrier' is rarely if ever used in mainstream residential construction, and it really should be.

Vapour retarder latex primers:

Firstly, the classification of a material as either an impermeable ‘vapour barrier’ or a semi-permeable ‘vapour retarder’ is determined by how much water vapour passes through the material under specific conditions.

There are vapour retarder primers on the market that exceed the requirements of the National Building Code of Canada & local US building code regarding water vapour diffusion, with a vapour permeance in the area of 30 to 36 ng, which is about half of the 60 ng often allowed by code.

|

|

Vapor barrier primer meets building code © Ecohome

|

So concerns that primers are insufficient to control vapour diffusion are unfounded, they just aren't widely used. But keep in mind that the construction industry can be slow to adopt new practices, regardless of the merits. So don't be intimidated if you want to break the norm.

Air leakage:

Now that we have looked at some options regarding vapour barriers time to understand the difference to air barriers, and firstly it should be pointed out that the water vapour permeating through building materials - the reason for installing a vapour barrier - is not the monster it has been made out to be. 100 times more water vapour is carried though a wall assembly by air leakage, than is carried by vapour diffusion. So the air barrier is 100 times more important than the vapour barrier.

Therefore, we really don't need to go to the extremes that we do regarding vapour barriers, as it actually takes the focus away from what we should be thinking about, which is creating an effective air barrier.

So here is the summed-up case for the “poly-free” house, and a bit of perspective:

- Water vapour diffusion through building materials accounts for only about 2% of moisture penetration through walls, and a vapour retarder primer can be twice as effective as it needs to be.

- Polyethylene is some 15 times more resistant to water vapour diffusion than it needs to be; it's expensive to buy and install; is environmentally questionable; and it can actually cause problems in the summer months.

In much of the country, you could take the time and money you would have spent on installing polyethylene on the entire exterior wall of your home, and instead put those resources into a latex vapour retarder paint on primer and a properly sealed air barrier. There are hard cost savings to be had doing this, and an improvement in both performance and durability.

The one glitch in the system, is that building inspectors can also be subject to the same conditioning that a lot of builders are, and do not realize that in many cases there are better options available than polyethylene for controlling water vapor in homes. When you take your plans in to get a permit, make sure it is clear what material you plan to use for water vapor control, so that you can go into battle then, and not during a home inspection after construction is complete.

References:

Lstiburek (2004):

U.S. Building Code requirements for vapor retarders are proposed based on climate and properties of other materials in the wall assembly. Identified hygrothermal regions include those applicable to Canada. Most assemblies do not use polyethylene and incorporate latex paint or vapor semi-permeable interior finishes.

The following main principles are recommended:

- Avoid vapor barriers where vapor retarders will work, avoid vapor retarders where vapor permeable materials will work.

- Avoid the installation of a vapor barrier on both sides of the wall assembly.

- Avoid using poly, foil faced batts, reflective barrier foils, and vinyl wall coverings on the interior of air-conditioned assemblies.

- Ventilate enclosures

Now you know more about vapor barrier paint and vapor retarder primers. Find all you need about how to build the best walls in the Ecohome Green Building Guide and in these pages:

Find out here about the benefits of a free Ecohome membership and sign up to get preferred pricing on select materials! |

Thanks for this .

I have a question regarding a SIPS (structural insulated panel) cabin structure...wanting to have the best solution for both air and vapour barrier, as well as a warmside surface sealer to eliminate any emissions from the OSB used on both sides to make the panels.

I'm in central ontario, and i imagine i should have little to block anyway, either way, because of the inherent nature of EPS (extruded polystyrene), so would tyvek outside and an interior vapour paint be overkill ?

What product is recommended, and where can i buy it

Walls, floor and ceiling are all around R29 value....160sq' floor.

thanks, fredpalmer

Hi Fred,

Just to clarify, XPS is the extruded, where EPS is expanded. I say this not to split hairs, just to make sure we are on the same page. Your sips are in all likely hood expanded (EPS) also known as bead board. I think you will successfully solve your moisture diffusion issues with the vapour retarder primer,as the rate of moisture movement through EPS is pretty slow on its own, as it is through OSB. In fact at 3/4 inch, OSB is accepted as a vapour barrier by building codes. I always like to point out that moisture diffusion through solid materials is a relatively small problem, where air leakage is a huge problem. Panels themselves are airtight, just be sure that your joints are well sealed. I have seen some pretty nasty failures of SIPS joints that can cause serious moisture damage. as for tyvek, an additional air barrier is never overkill, as long as it is breathable, as Tyvek is. You can also use building paper in this regard, what you mostly need outside is a drainage plane. Be sure to install vertical strapping to make sure any moisture that penetrates can drain away. And if you really want to make an airtight house, I would suggest taping the OSB joints, which will give you added protection against air leakage. Don't bother doing this with conventional building tapes, they don't last. You'd need to look into solvent free building tapes, SIGA is one brand that comes to mind. To the best of my knowledge there aren't any manufacturers in North America that make them, the good stuff comes from German or Switzerland. But in a short time they will pay for themselves in heat savings, not to mention preventing moisture damage. As for where to buy it the primer, I would check with manufacturers, you won't find it at box stores. Here is a bit more on SIPS to make sure you get a good final product http://www.ecohome.net/news/latest/creating-air-barrier-sips-roof Hope it helps!

My daughter has a 100yr old house with lathe and plaster walls and ceilings. There is blown cellulose over old fibreglass in the attic,not a lot though. There is no vapour barrier. I was thinking of moving the insulation aside and placing poly in each joist space, sealing the poly to the joists with acoustic caulking and a placing new batts back in covered by the blown insulation.

The soffits have been opened and vented with foam vent channels.

Would it be prudent to also use a vapour retarder primer on the ceiling as well or only that product.

The walls have no insulation. I have read that blowing in insulation invites moisture to settle in the insulation over a period of time if there is no moisture barrier behind the lathe and plaster and it is not cost effective as insulating the ceiling to code.

Can a vapour retarder paint be applied over old paint?

Hi Robin,I think you're really going to like me after this answer....

She does too have a vapour barrier, in the form of 100 years worth of oil paint. Oil paint does the same job as the vapour retarder primer, it's just really nasty stuff that we prefer not to even suggest. But since it's there already, you're good. I would suggest putting fresh paint over it, but more to seal any lead in, certainly where you can touch walls if not the ceiling.

Other than ensuring the cellulose doesn't impede air flow on the sides, I would leave the attic as is, maybe blow in a bit more cellulose if you think its insufficient.

Roxul has a product called 'rockfill' that is specifically designed for attics, and if you want to top it up a bit this might be the answer for you, its all done by hand. They have an ad that will pop up on rotation to the right of the page, there is a video on there of it being installed. Despite the fact that the guy in the video isn't wearing a mask and glasses, I would be if I were you.

When it comes to walls, again a century of oil paint will stop moisture diffusion so there is no problem not having a vapour barrier. A much bigger source of moisture in walls than vapour diffusion is air leakage, so that is something you can tackle pretty easily. Get a bunch of caulking and go crazy. Do the tops and bottoms of baseboard mouldings, around windows, and maybe even get electrical box covers with gaskets. But densely packed cellulose is really the best option for upgrading old walls.

Since you can't actually see what is going on there is the risk of omitting areas, a thermal imaging camera can quickly tell you if it is well done, and will point out any spots that weren't done right. Some installers have them, if not home inspectors sometimes do as well, you could probably get someone to look it over afterwards for a fairly reasonable price. Good luck!

So my home built in 1938, Lath and plaster - I have stripped the exterior sheathing down to the studs. I am planning on filling the now empty stud space with R13 Batt insulation, 7/16 OSB (Sturctural sheathing) 3/4 RMax (foil facer both sides) Foil tape obe thejoints, covered with LP Smartboard lap siding, paint.

I assume based on your previous reply, that the oil base paint (layers?) plus the Acrylic paints/primer would serve as an adquate VB for the inside.

Do you see a problem with my approch?

Hello Mike,

First, I hope that you still monitor this blog as the subject is quite interesting to me as I have just been exposed to the concept today. While visiting a custom modular builder in the states,they are using a special primer with the vapor retarder system rather then the standard poly.

My question is, given the fact that today it is September 2014, where does the Ontario Building Code and thus the local Building Inspector/official stand on this subject. I like it, especially with high end HRV systems being used which assist in regulating the moisture and air quality.

I look forward to your current feedback and thank you for speaking on this subject.

Cheers,

Lorne

mike great info. I have been reading material for weeks on moisture control through foundation walls but no one addresses the fact that the outside temperature may change a lot, which means the poly has to be in two places. I also heard that's called a diaper wall, which is wrong. I thought about the primer I might do it depending if it has a smell to it. good article I found it very informative. I also read that some students at George brown are performing an experiment as we speak on vapor barriers, they are trying to get the building code to change. the experiment (done in a persons house) was having an exterior wall finshed with the ruxol insulation, with a 6mil poly over the ruxol insulation. the only difference is that they cut the top portion of the poly and taped a very low quality vapor barrier in its place to allow it to breath a little.

Wow there is a lot of good information here. Thank you for writing this. It is helping me understand where moisture can build up.

Hi there, we live on the gulf islands, building a new home as owner builders and figuring it out as we go. I worry that being in such a damp environment for so much of the year, we could have an issue with mould, as other neighbors (a professional builder) who used plastic Vapour barrier have had mould show up in less than 2 years on his north wall. How can we avoid getting mould?

Hi Rose,

That's a great question, so I've moved it to the advice column and answered it there in case others in your climate are facing the same challenges. You can find it at this link.

I had Just purchased a home built in the late 1960's. I am going to place new drywall over the old drywall in the ceiling. There are many hole in the old ceiling as previous ower had plants and other decoration hanging from the ceiling. Currently there is 4 mil poly and approx. R40 insultation in the attic. is it acceptalbe to place another layer of poly between the old drywall and the new drywall, or should I use a moisture retarding primer

Hi Raymond,

Given that you are are looking at vapor retarder primer as an alternative, then I would say no, you don't need an additional vapor barrier to the existing 4 mil poly. Even if there are holes in it or it isn't properly taped, that would be of little consequence for vapor diffusion (read here about the difference between air barriers and vapor barriers). My bigger concern would be an air barrier since that 4 mil poly is almost certainly employed as the vapor barrier AND the air barrier. So if it's not doing it's job as an air barrier, then you need to have an air sealing strategy, which can simply be the drywall.

If you are careful to seal around openings like light fixtures and ceiling fans, and seal it well at the wall junction, then your new layer of drywall can act as an air barrier. And since you already have the 4 mil poly vapor barrier I would just use a standard Low VOC paint.

If the walls are sufficiently insulated, warm moist air will not hit a cold surface and condense. This sounds like an eco-home.

I've noticed some thermal tracking on my vented cathedral ceilings towards lower-half where the ceiling meets the wall. My assumption is some of the fiberglass batt insulation was cut too small or slid. Assuming the best option is to cut the sheetrock out in those areas an replace the batt insulation (not fun). As a temporary fix to stop possible moisture from passing through these areas, would a vapor retarder latex primer on the cathedral ceiling help stop moisture? I found Start Right Interior Latex Vapor Barrier Primer and Benjamin Moore Super Spec Latex Vapor Barrier 260.

I have a question. What would you use on bare interior basement concrete floors and walls if you plan on leaving them unfinished? Does waterproofer have the right perm rating, what product do you use in this case? If and when I plan to build eps and framed wall in front of this will this paint be on the wrong side? I'm in nyc metro area. Thanks, Joe

Hi Joseph If you're not going to insulate the basement right away I don't know that I'd put anything up on the walls right now. if you had high radon gas in your basement you might want to consider a membrane like 6-mil poly to mitigate it, but to reduce radon you would need to do the floor as well. At the moment the walls would be drying to the interior a bit, but it wouldn't be any more than a dehumidifier would be able to handle easily. When you get to it, the Rigid EPS foam insulation against the concrete foundation wall will act as a vapor barrier as long as you have at least 2 inches.

My garage ceiling is drywalled and taped. My thought was to blow in insulation and use vapor barrier paint on the finished side. Would this be sufficient? Do you have a recommended product?

Hi Ryan, I can't say for sure if it would be sufficient, safest is to do a poly barrier but I can see how that's a problem. We used a vapor barrier primer from Benjamin Moore. The one less than idea thing about vapor barrier paint and primer is the complete inability to apply a uniform coat. So unless you are cooling your garage in summer you should have no need to have it at all breathable like in the article here, so I would do an extra coat or two to be sure.

I'm on the verge of madness. This has been a lifelong battle which I haven't figured out yet, but coming to THE answer with your article here, I hope!! -->

My house (c. 1948) is brick with solid masonry walls. No air cavity and no vapor barrier. Parged interior walls. I've lived here most of my life, moved away, then bought the house after parents died. I remember as a kid my mom saying the house was damp and had mildew problems. Now that I live here solo I can say, this is a terrible problem, OMG, I had NO idea. The first floor definitely has mildew issues at the bottoms of the interior outside walls. This is everywhere! And worst in my opinion, are the three closets on an outside wall. It is unbelievable how clothing gets RUINED in those closets. Orange rust stains, and mildew spots, all over the clothing, especially where clothes were closest to the wall. When I first saw this problem, I invested in a ton of DampRid, placing them all over the closets and interior space. This only was a small bandaid on the problem.

Three years ago I bought small dehumidifiers for the corners of the closets, and what I collect each week from all three units is a total of SEVEN cups of water!! Every single week, from Spring to Fall, it's the same amount of moisture, with or without rain. So this is from humidity. (I'm in Zone 4.) The little dehumidifiers have helped the problem about 90%, but there are STILL tiny mildew marks and rust stains on *some* clothes.

Sounds to me like I should paint a good thick coat of vapor retardant on the inside of these closets. Maybe the entire 1st floor! (The 2nd floor doesn't have this prob.) And caulk any air leaks. I'm at my wits end over this!! Some day I'd like to sell this house but I don't want the new owners to be stuck with this nasty problem. The mildew even collects on shoes and boots. Could/should I use waterproof masonry creams on the exterior? Though these may not stop humidity intrusion.... I've asked local professionals, each has a different solution. I'd love to know your opinion!

Thank you for this very informative and helpful article!! Any help is greatly appreciated!! <3 <3 Thank you.

I have a room that we closed up and now the concrete is getting wet, i guess because the room is closed up with no real air flow , could a latex vapor barrier paint or primer solve this or will i have to put air conditioning in there..

<... put those resources into a latex vapour retarder paint on primer and a properly sealed air barrier.>

Okay, I'm sold on the latex vapour retarder. What sealed air barrier would you recommend?

I will be placing mineral wood batts between the ceiling joists of a 5.5 ft high unfinished basement. Prior to doing so, I suppose I could spray (with a gun) the latex vapor retarder pain on primer. Right?

Thanks!

-Ron

I have stucco exterior walls and fence in az

there is a bad odor coming off it

is there a product that can seal them and block the odors?

thanks

Hi there! Happy I found this. Can you please elaborate on this point you mention "Avoid using poly, foil faced batts, reflective barrier foils, and vinyl wall coverings on the interior of air-conditioned assemblies." Thanks!