As a precursor to a new post exploring everything you wanted to know about Dry Rot but were afraid to ask, we wanted to cover the causes, effects and solutions for interstitial condensation in walls and roofs. We’ve all heard of condensation, but has anyone ever heard of interstitial condensation? If you haven’t (or even if you have) have a read of the below.

What is interstitial condensation?

Interstitial condensation is a form of damp that occurs most often in winter when warm, moist, internal air from inside a structure finds its way into cold exterior walls, floors or roof and ceilings. It can also be caused in in summer months in conditions of high external humidity in combination with heavily air conditioned homes that have interior poly vapor barriers - but more of that below.

First, a basic science lesson - when air cools down as the temperature drops, it releases moisture as condensation. This is known as the dew point temperature, and for interstitial condensation this condensate (or release of moisture) occurs within the core of the wall, forming water that soaks into building materials.

This may sound just like the surface condensation you would see on windows, however it is not. While the mechanism is the same science as surface condensation, interstitial condensation forms in the core of home structures. This causes damage we can't typically see until most of the damage has been done and the only remedy is often an extensive and costly rebuild, which is why it's important to prevent it in the first place.

You also have to be careful with central air conditioning systems, or ventilation systems with any element of humidity control, as we've seen internal structural damage caused by high humidity from leaking drains. Despite this also technically being water forming due to condensation, this is actually a mechanical or installation failure and shouldn’t be confused with an interior condensation problem.

Can interstitial condensation be caused by central air conditioning?

Yes it can, but unfortunately most HVAC installers won't tell potential new central-air clients about that fact. Polyethylene vapor barriers in combination with air conditioning in homes can rot walls because of the condensation they may cause.

This is why if you have a newer home with an impermeable poly vapor barrier, you are at risk of drawing warm and humid exterior air into your wall assembly where it can condense on that cold poly surface. This is unfortunately a standard building practice in cold climates that also have hot humid summers. And the colder you keep your home the greater the risk, so our best advice in such a situations is to use your AC to take the edge off, but don’t set the interior temperature to frigid temperatures.

Another fix to that problem would be when the day comes that you need to replace exterior siding, when you can add some exterior rigid insulation to the walls as a means of keeping your home cooler in summer.

Remember, Insulation is the gift that keeps on giving, long after that fancy new central air conditioning system needs major servicing or replacement! To read all about why not to install central air in homes with a poly vapor barrier, see here.

Does interstitial condensation cause damage?

Yes, interstitial condensation can lead to damage in homes, the moisture deposited in walls or roofs can lead to rot, mold and hidden structural damage.

Just like dry rot, Interstitial condensation can be difficult to diagnose due to the fact that it’s hard to notice any signs of a problem until significant damage has been done. As we always say with potential structural issues, if you think you have a problem it is best to have a competent professional assess the damage and formulate a solution.

What are the signs of interstitial condensation?

Here are some things you can keep an eye out for so see if your home is potentially at risk of interstitial condensation in walls or roofs:

- Cold spots on walls, due to the reduced thermal efficiency of insulation that is saturated with moisture.

- Mold growth, which is a cause of respiratory allergies.

- Mildew - most frequently found as black spots on drywall, especially behind furniture.

- Staining coming from behind drywall and around baseboards and any junction points in walls.

- Corrosion of building components.

- Frost damage to exterior finishes, roofs or masonry.

- Poor performance of insulation and reduced thermal resistance of other elements of the building fabric. This in turn can reduce the temperature of the building fabric, exacerbating the condensation problem.

- Efflorescence, which is the crystalline deposit of salts and minerals left behind when water evaporates.

- Liberation of chemicals from structural building materials - like copper staining from treated timbers.

- Internal damage to equipment with metal casings - like heating components or fireplaces which penetrate walls.

- Electrical failure caused by internal corrosion of components like junction boxes or pot lights.

One majorly noticeable problem to look out for in cold climate zones is frost and ice damage. This happens when the water droplets formed by interstitial condensation freeze and expand, causing damage to masonry elements or cladding. If this happens its very likely to have caused internal structural damage too.

How do I stop interstitial condensation?

Like we said earlier on, and as much as we hate it, Interstitial condensation has a sneaky way of creeping up on you and it doesn't usually become noticeable until significant damage has been done within walls or roofs. As with anything structural and to do with homes, the cost to repair this damage can be extremely high. It sure sucks to be homeowners sometimes!

The good news though is that there are ways to prevent it so you can avoid these issues and costs. The most important thing is to keep the humidity levels in your home low enough, aim for below 40% Relative Humidity (RH), so step one would be humidity monitoring, followed by installing adequate heat recovery ventilation, and a dehumidifier sized properly for the volume of air you need to condition if necessary.

Ironically, interstitial condensation is more of a common issue in new, modern structures than older structures. This is due to them being built to be both warm and cool, whereas older homes were built with more permeable materials and have lots of natural ventilation and draughts.

So unfortunately for those with newer built houses, you’re not out of the woods. This isn't to say that older houses won’t be affected though, they absolutely can and it’s usually caused by building defects or lack of insulation causing cold floors or walls.

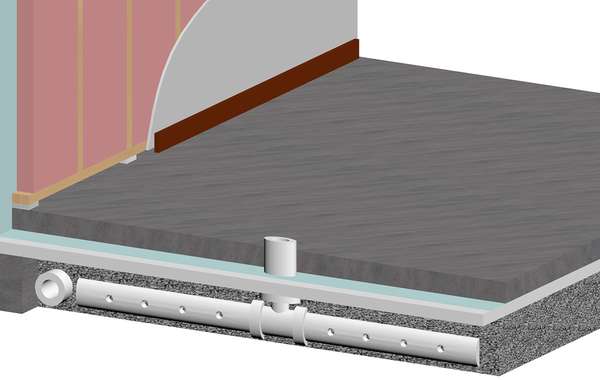

- Vapor control layers (VCL) or membranes should be positioned on the warm side of insulation, however, these layers must be carefully sealed and penetrations avoided to prevent air leaking. (See here to understand the difference between air barriers and vapor barriers.)

- Materials with low vapour resistance should be positioned on the cooler side of the construction (although this can be problematic where for example the external siding is impermeable - another reason we encourage readers to carefully choose the right exterior siding).

- Ventilated cavities can be provided near the cooler side of the construction by correctly installing siding.

- Cold bridges or thermal bridges should be eliminated wherever possible within the structure.

- The moisture and relative humidity in the building itself should be reduced by replacing flue-less gas or oil heaters, improving ventilation and so on. Ventilation can be humidity activated by using a hygrostat, and is best controlled by a careful choice of HRV or ERV.

- The internal temperature of the building should be kept as even as possible - if the external envelope is well insulated and maximum use made of passive solar heating by design, try to avoid having certain rooms very warm and others cold.

Of particular importance is controlling the level of moist air in your property, it stops condensation forming within the walls and surfaces, so if suffering from excess condensation on windows, you really do need to get to the bottom of it rather than mopping it up every day. It will also provide you with other positive effects such as indoor air quality and energy saving benefits! It’s a win-win really!

So if you’re looking into doing some home renovations and want to avoid any unwanted repairs and costs then we say invest in a ventilation system if you don’t have one, there are countless benefits for health, durability and energy efficiency.

Now you've learned all about interstitial condensation in walls and roofs, why it happens and how to prevent it, read more below about other home humidity problems and solutions:

Read more about sustainable and durable home building in the Ecohome Building guide, and reap the benefits of signing up for a free Ecohome network membership! |

Hi there, thanks for the article.

We recently moved in to a house (Ontario, Canada) with a 2x6 wood foundation filled with R-24 batt, c/w poly. vapour barrier (V.B. is poorly sealed at windows I noticed). We are now noticing some condensation on the inside of the V.B. on the wall that gets the most sun throughout the day. We have a dehumidifier running in the basement as well as an HRV.

My question would be what you recommend to remedy this and stop it from happening in the future, as well what you think the best practice is for a wood foundation in terms of vapour control.

Thanks in advance!

Hi Brendan,

Just to clarify - I think you mean you have a concrete foundation with a 2x6 framed wall on the inside, correct? I'll run with that assumption. Wood foundations are pretty rare but they do exist.

What would be great to see in a foundation would be some sort of vapour protection separating the wood from the concrete, is there anything behind the wall like Rigid foam boards, tar paper, Tyvek, anything? Basement walls should not have vapour barriers on them, but unfortunately most do. Here is our page on why basements are moldy and how to fix it, have a read there to see what I mean.

Since the ground is wet and not many older homes have exterior foundation membranes, the concrete usually stays wet. So the only place for the wall to dry to - which physics demands it to do if it is adjacent to anything more dry - is to the interior. That is likely what is happening, but the poly stops moisture from evaporating into the air where your dehumidifier can manage it.

So the not great news, is that the poly vapor barrier is the problem, just like every other basement. And there isn't much you can do short of remove it, and that would in most cases mean a full basement renovation and rebuilding it properly.

Building basements with vapor barriers on the inside is the biggest consistent mistake made in home construction. And is your basement finished and furnished? One thing that can help is removing strips of drywall as well as strips of the poly every few feet or so around the basement to let the moisture out. This will be, however, a little unsightly if it's part of your home's living area.

But to ease your mind slightly maybe, at least know that you are not alone. Most basements are moldy because of this very reason. So keep running your dehumidifier, and hopefully the smell isn't too bad down there until the day you decide to redo the basement, at which point you can build it so it can dry to the inside.

Good Morning! To avoid condensation within walls, where and which what type of vapor barrier should be on the walls and ceiling of an attached garage (with rooms above)? The garage will have minimal heat but no air conditioning. We are near Montreal so cold winters, hot humid summers. The house has central a/c & heat and an ERV. Thanks! Roger