Basements, downstairs in more ways than one

For those wishing to become homeowners, one of the decisions you'll face when buying a new property is whether or not to choose a home with a finished basement. This decision can have significant implications for your lifestyle, your finances, and your quality of life.

We will explore the pros and cons of purchasing a home with a finished or unfinished basement, for both new and old homes. First I’d like to cover a very short history of how this ‘basement culture’ arose, so you can see whether or not this is a trend you want to follow.

Many early 20th-century homes, especially on the Eastern Seaboard, remain occupied. We'll use them as a jumping-off point to explore the evolution of the modern home, and what are affectionately known as 'man-caves' across North America.

The history of the finished basement

In colder climates like the northern US and southern Canada, building code requirements for footing depth would usually be somewhere about 3 to 5 feet below grade, enough to get below the regional frost line in order to prevent buildings from heaving as moisture in the ground freezes and expands. The colder the climate, the deeper the frost penetrates and the deeper the footing needs to be.

So basements were originally just a durability measure to keep homes from shifting, and walls were only built tall enough to accommodate mechanical systems like furnaces, water heaters, and laundry machines. Other common uses were as root cellars for cold food storage space or as coal cellars or wood storage for the cold winters. But there was no intention originally, as evidenced by the height, to use them as functional living space.

Modern home construction now almost always begins with a standard 8-foot-high foundation wall, compared to an older home which often has ceilings barely high enough to not scrape your head.

Do we need basements now?

In a word, or really two words, we don’t. We now have rigid foam insulation, and an inch of it is equivalent to about a foot of dirt. And ever since the advent of insulation, there is no actual need for basements in terms of ensuring footing depths are below the frost line anymore, as you can easily just move the frost line to above a sheet of insulation laid flat on the ground. So a basement foundation is now a matter of personal taste, quality of life, and in dense urban areas, home size and property value are linked to maximizing sq.ft.

As for durability and risk of bulk water and moisture damage or worse still basement flooding, there is no case whatsoever to be made in favor of digging a deep hole into which we seat a house. A slab-on-grade is always the more durable foundation, full stop. The only reasons left over to build a basement are - personal taste and wanting a dark cool retreat in your home, and to maximize home size within the limitations of regional bylaws and space limitations.

By that last point I mean – building a new home on a small building lot in an urban core can limit your options in terms of home size. So, for many families, as well as for resale investment purposes, it makes sense to take advantage of an additional lower story to increase occupancy space, despite the potential risks and drawbacks of having a basement - not to mention the potential liability.

Choosing between a basement and a slab-on-grade

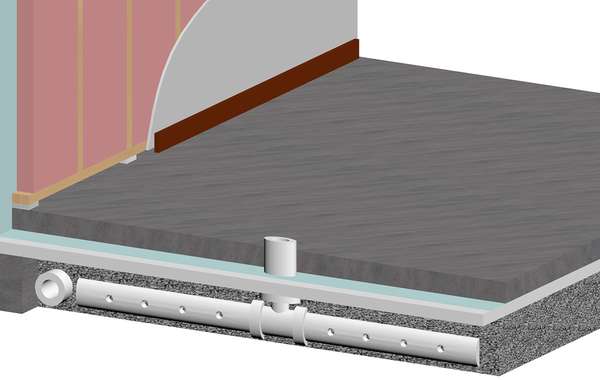

Many people would not even know there is an alternative foundation to a full basement, but there is. A slab-on-grade, also known as a Frost Protected Shallow Foundation (FPSF) is a concrete slab foundation laid on grade, and all exterior walls are above grade. Flat sheets of rigid insulation are laid in a skirt around the perimeter to eliminate the risk of frost heave.

The R-value of rigid insulation is about 8 to 10 times higher than dirt, so you don’t actually need to go down 4 or 5 feet to avoid frost heave. You can accomplish the same by laying down a skirt of insulation on the surface, perhaps 2, 3, or 4 inches thick, and covering it with a few inches of fill.

This is why it is possible to build a slab-on-grade or frost-protected shallow foundation and keep your entire home above grade. You do that by using ‘insulation’ as insulation, instead of using dirt as insulation, so there is no longer any need ever, in terms of frost protection, to build a basement.

There are cases where builders talk homeowners into digging below the frost line for the footing of a slab, then pouring ‘frost’ walls, filling the interior of that newly built foundation, and pouring a slab at the top. To us, that seems like a colossal waste of money or opportunity, as you may as well at that point divert the cost of backfilling to building a floor and just have a basement. You can read all about choosing between a slab on grade and a basement foundation here.

Important note: the thickness and width of the insulation skirt are very important and should be determined by a design professional such as a geotechnical engineer to ensure it is suitable for frost protection in a particular climate. Insufficient skirting will still leave you at risk of frost heave.

How to build foundations on high water tables and expansive soils

Another downside of basement foundations that don’t get a lot of air time, is that without knowing what is below the ground, you are flying blind in a way, and you may come across surprises. Staying close to the surface means less chance of having to deal with high water tables or large rocks that may need removal before continuing work. See our page on how to build foundations and slabs on high water tables and expansive soils.

The reason to build a basement for a new home

Maximizing home size with infill construction projects in urban city cores is a very smart use of developed land. Roads are already built, and the power and water lines are there, as are public transportation systems, schools, and shops. Urban densification instead of sprawl is a smart move all around.

So if you can squeeze more living space out of a city lot, you absolutely should do that. It can accommodate larger families, in-law suites, or rental apartments. In such cases, it can be worth the downsides of basements, and worth the added investment to build a basement to a higher standard so you reduce the risk of failures.

And not to be ignored, is the benefit of having a third level of living space in the standard two-story home. Further proximity from upper-floor bedrooms offers great privacy and sound reduction. It’s not that you can’t accomplish the same thing with design features in a slab-on-grade home, but it’s a ready-made clear advantage of a basement in a family home.

Reasons not to build a basement for a new home

Basements are notoriously humid, always at risk of flooding, and they have limited natural light. It is more expensive to build below grade than above grade, so if you don’t have to, it’s worth considering alternatives.

What I just said about it being cheaper to build above grade will no doubt be challenged in the comments by builders, and I welcome it. I will qualify that point by saying this - if you build a basement properly – energy-efficient, mold-free, and include resiliency measures to protect basements against flooding, water and moisture damage, that is what costs more.

Most homes that have been built by garden-variety home developers typically have very few of those essential features because a lot of them are not required by code, and that is why the majority of basements are failing, or will fail, whether the homeowners realize it yet or not.

The intention of building codes is to protect homes and their occupants, and in most areas they must be carefully adhered to, even when they make no sense, which can often be the case with basements.

First-time readers in here would not know what I mean by such a bold statement, but the short story is that despite what building code may say, adding a polyethylene vapor barrier behind drywall on basement walls is the last thing you should ever do, yet still a common practice.

Here is our page all about how to build basements and avoid mold so you know why almost all basements fail, and what a proper basement would be like instead. We hope these articles will leave you with the tools to spot a future problem and avoid spending your life savings on purchasing a future problem. We even have a guide on what to do if you're unfortunate enough to have a basement flood.

Why basement walls are wet

Concrete is porous, and will absorb moisture for as long as it has a source. Most basement construction fails to take that into consideration, and walls are built that are doomed to fail. Even the best-built basement that has flawless exterior moisture protection will still take at least 5 years to fully dry. So if you buy a brand new house with raw concrete walls, what you see is actually about 50% water. And if you slap a bunch of 2x4s with some insulation against it and then a sheet of plastic, your walls will rot.

What to look for in a basement when home shopping

The lure of pot lights, pool tables and home theaters is what sellers want you to look at when they take you down to a basement, but what you should really be looking for are the problems that are lurking behind the walls. In the early years after construction, there will be little to no sign of the looming failure you are considering purchasing; it will take a few years for mold to develop to the point where you will notice it with your eyes and nose.

When you walk up to a house for a first visit, take a look at the foundation and see what moisture protection exists. If you dig your finger an inch or two down and see black tar on the walls, that is helpful and better than nothing. Much better than that would be a dimpled waterproof membrane (as seen in the main image above), but that is unlikely in anything but high-end custom builds.

On the inside, look for an unfinished portion of wall to inspect. Somewhere in a storage or mechanical room, you should find at least some spot without drywall so you can see the bones of the house. What you find may be rigid foam, metal or wood studs, fiberglass or mineral wool batt insulation, probably (and regrettably) covered with a vapor barrier.

If there is moisture buildup evident on the interior side of the poly vapor barrier, that means there is a lot of water in the walls and it’s only a matter of time until all your wood studs rot and your basement becomes dank and smelly.

I personally would see if I could slice in the poly vapor barrier with a utility knife (and tape it closed again) so I could feel behind. If it’s rigid foam, that’s great news. If it is just raw concrete and it feels clammy, I would go look at the next house on your list.

If you see no humidity or water but you see signs that there was some previously, such as efflorescence or stains, that’s another indication that there may still be a problem that may only be seasonal. But it may still be humid inside.

Efflorescence is a white and often powdery building up on concrete floors or walls. It is harmless to humans, but it is an indication of water issues. When there is any type of moisture movement through walls or floors, it solubilizes salts and other minerals in the concrete, which are then left on the surface after the water or moisture evaporates.

Evaluating a home before purchase - how to spot potential problems

When should you insulate and finish the basement of a new home?

Some builders, aware of the moisture content of new foundations may suggest waiting a couple of years to allow the moisture to escape. That is sage advice to receive if you plan to build it with a poly vapor barrier as it would push back the mold > demolition > renovation a bit, but if you follow logical building practices there is no reason why you can’t do it the right way. Freshly poured concrete is mostly water, every square foot holds a gallon of water or almost 4 liters. A third of that will react with the concrete, a third will dry in about a month, and the last third of moisture will slowly be released over the next 5 years or so, and that is only if the foundation exterior and footings have been meticulously protected from the wet ground.

If you take possession of a brand-new home with perfectly sealed and protected footing and exterior foundation wall, and you immediately put wood and insulation against it and cover it with a sheet of polyethylene vapor barrier, you can expect mold since it is still full of water.

If you have an older unfinished basement that seems dry and you put wood, insulation against it, and a sheet of poly you should still expect mold, as it almost certainly has a footing sitting in wet ground sucking up moisture that will migrate all the way up the wall.

In case it isn’t already abundantly clear, I’m going to drive this point home – the biggest problem is the poly. If you remove the poly from the equation you remove most of the problems in basements. That allows moisture to escape and be handled by dehumidifiers and ventilation systems. Vapor barriers never should have made their way down into the basement. That simple mistake is causing an easily avoidable and catastrophic failure in the North American house stock.

Home features of a well-built house and basement to look for and ask builders about

- Exterior waterproof membranes

- Eavestroughs that direct water far from the home

- Grading to divert surface water away from the home and not toward it

- Interior stud walls raised off the floor for protection from moisture and minor flooding

- Poly or foam directly AGAINST the concrete to keep moisture away from framed walls

- Lack of a vapor barrier – either none or a breathable membrane.

- Drywall placed against studs that allow moisture to pass through and be removed by ventilation systems and dehumidifiers is ideal

- Sump pump or even better, a sump pump with battery backup

- Smart home alerts of flooding so you can respond quicker

- Sewage backflow valve

Buying a home with an insulated but unfinished basement

Depending on the climate you live in, new home sales may include bare foundation walls, or in colder regions it will often be required that homes have basement walls insulated before delivery. If that’s the case and your basement has a stud wall, insulation, and vapor barrier, you can make simple and very cheap improvements by ripping off the vapor barrier. Yeah, I know it’s challenging to wrap your head around that bold a move since most houses have one, but it really is that bad.

The entire premise of adding vapor barriers to homes is to keep the walls dry so they don't rot. In the image below, does it look like the vapor barrier is keeping the wood and insulation dry? it most certainly is not, and this basement is on the fast track to an expensive renovation. Vapor barriers below grade trap moisture in walls and that makes no sense. You should let the moisture out. See here to learn why you should never put a vapor barrier on the interior of a basement wall.

If your basement floor is unfinished, you might want to consider adding a radiant floor heating system, as it would be a great way to make the space more comfortable.

Buying a home with bare concrete foundation walls – how to finish them

You will still see a home occasionally with full height but unfinished bare concrete walls. This is in our opinion, a really good one to score since the walls would be much dryer than a new one and none of the standard mistakes have been made yet.

Unless you can see building plans for photos from construction, you will never know if it truly is water-proofed properly or has proper drainage, so assume it doesn’t.

You should look around for signs of previous water infiltration, but even if there are no signs, build as if it is high risk. Here is our page on best practices for basement finishing in new home construction where you will see diagrams on how to insulate a basement properly on the interior.

Conclusion on when basements make sense and when they don’t:

In our opinion, for infill buildings in dense city neighborhoods with close neighbors and height restrictions it would be a lost opportunity to build a home without maximizing the space with a basement.

For any new build that isn’t subject to height restrictions or close neighboring setbacks, it does not in our opinion make sense to needlessly add the cost and risk of sticking your house in a wet hole in the ground. What is the point? A home above grade eliminates so much risk from flooding and moisture damage. If you are going to build a basement, just be sure to do it properly.

Now you know about what to look for in basements when home shopping. Find more pages about basement finishing, basement flood prevention and what to look for when home shopping on the pages below and in the Ecohome Green Building Guide pages.

Find more about green home construction and reap the benefits of a free Ecohome Network Membership here. |

Hi there, You refrenced a second article "Best Practices for Basment Insullation for New Home Builds". For builds with and without exterior isullation, it recommends latex paint as a vapour retarder. To me that is conflicting with this article as it would not let the water from the concrete escape into the home. Can you explain why this is may be recommended but a proper vapour barrier would be, or is this a differnece of opinion? Thanks for all the great info

Hi Carter

A vapour retarder slows moisture but it doesn't stop it entirely. So in a basement if there is a lot of moisture in the wall then latex paint will let it escape, but at the same time if you happen to have a spell of very high humidiity in the interior air then it will protect the wall from absorbing it.

Another solution is a smart membrane vapour retarder instead of a vapor barrier. It has pores that open when moisture is very high in order to let it pass. A lot of home inspectors still insist on seeing a vapour barrier in basements despite the harm them do, so if you have a 'smart' membrane it will give the inspector the visual they want without trapping moisture in the walls.

Building in a hole in the wet ground poses durability issues any way you slice it, so vapor retarders instead of vapor barriers is the more sensible way to go. best is to run a dehumidifier and keep the air dry so the walls can dry inwards. Better still would be for new home construction build a slab on grade and avoid moldy basements altogether.